Reciprocating Engines

Most small aircraft are designed with reciprocating engines. The name is derived from the back-and-forth, movement of the pistons that produce the mechanical energy necessary to accomplish work. Reciprocating engines operate on the basic principle of converting chemical energy (fuel) into mechanical energy (movement of the propeller). The two primary reciprocating engine designs are the spark-ignition engine and the compression ignition engine.

- Spark ignition engines use a spark plug to ignite a pre-mixed fuel-air mixture.

- A compression ignition engine first compresses the air in the cylinder, raising its temperature to a degree necessary for automatic ignition when fuel is injected into the cylinder. The majority of general aviation aircraft are equiped with a spark-ignition engine, therefore, the following discussion will be limited to the spark-ignition engine.

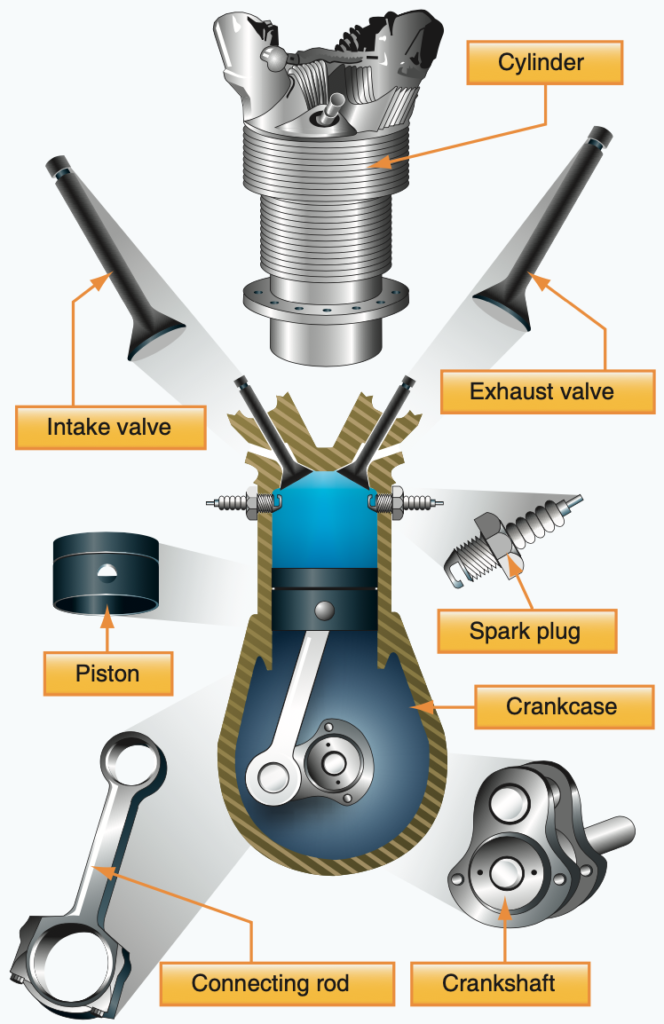

Engine Components

Spark ignition four-stroke engines remain the most common design used in general aviation today. The main parts of a spark ignition reciprocating engine include the cylinders, crankcase, and accessory housing. The intake/exhaust valves, spark plugs, and pistons are located in the cylinders. The crankshaft and connecting rods are located in the crankcase. The magnetos are normally located on the engine accessory housing.

Cylinder Arrangement

Radial

Cylinders are placed radially around the crankcase. This provides an improved power-to-weight ratio, which is a measurement of how powerful the engine is relative to its weight. The more powerful the engine and the smaller its mass, the greater the power-to-weight ratio. The large frontal area of [glosary_exclude]radial[/glosary_exclude] engines create more drag than other arrangement types.

Inline

Cylinders are placed one after the other along a line. This minimizes the frontal area of the engine and therefore drag, but results in a smaller power-to-weight ratio and cooling issues for cylinders toward the rear of the engine.

Horizontally Opposed

Horizontally opposed engines are the most popular reciprocating engines used on smaller aircraft. These engines always have an even number of cylinders, since a cylinder on one side of the crankcase “opposes” a cylinder on the other side. The majority are air-cooled and benefit from large power-to-weight ratios owing partly to its small and lightweight crankcase. Its small frontal area also allows for a configuration that minimizes drag.